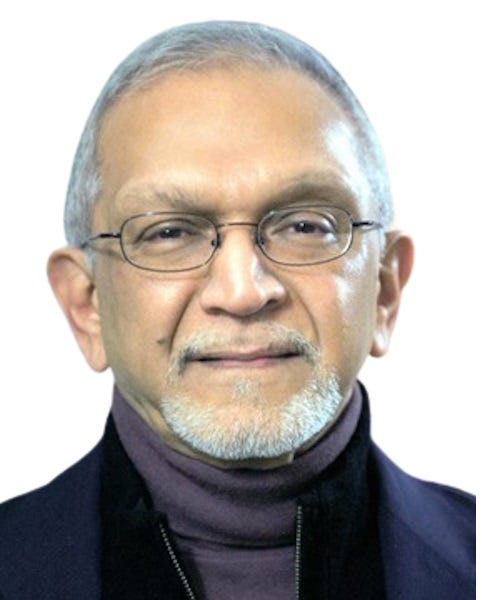

Abdulaziz Sachedina (George Mason University), "Islamic ethics: fundamental aspects of human conduct"

Oxford University Press, 2022

There have been two main traditions of writing on ethics in the Islamic tradition, one philosophical and related to the works of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, represented by thinkers such as Avicenna, and one theological, represented by such figures as the famous theologian al-Qadi Abd al-Jabbar. Some later scholars attempted to combine those two traditions. For the most part, however, the views of the jurists have been ignored.

In this book, I call attention to this third tradition of ethics, which has its home in legal literature. The problem is that Islamic jurists did not produce a genre of ethical manuals, and their form of ethics, which I term juridical ethics, must be derived or extracted from works that ostensibly treat legal rulings and obligations, or scriptural hermeneutics and legal theory. Presenting an outline of the version of Islamic ethics that is embedded in the textual legacy of the Islamic legal tradition, I argue that this juridical ethics is an important, even dominant form of ethics in modern Islam. As a matter of fact, this form of ethics has been challenged by modernity and I investigate the variety of ways in which legal ethical thinkers have reacted. How do Muslim religious leaders come to grips with modern demands of directing their communities to live as modern citizens of nation-states? What kind of moral and spiritual resources are being garnered by their scholars to respond to the new issues in sciences, more immediately in medicine, and constantly changing social relationships? To answer these pressing questions, it is necessary to go beyond the philosophical ethics of virtue and human character and acknowledge the importance of ethics to the formulation in Muslim interpretive jurisprudence of religious and moral decisions that are based on reason and revelation.

Why Islamic Ethics? Why not Islamic Juridical Ethics? Contemporary Debates about Ethics in Islamic Practice

The present study on Islamic ethics comes at almost the end of my career in academia. From all that I had studied in my history, philosophy, and Islamic studies courses I was confident that there existed a far-reaching connection between religion and ethics in Islamic tradition. My graduate work in Islamic studies further confirmed the contours of the debate among Muslim scholars who often deliberated about the priority of locating ethics as a fundamental source for deriving epistemic guidelines about human conduct. Historically, the critical question for Muslim religious thinkers has been to establish a logical epistemological relation between the two fields of law and ethics to validate a cognitively undeniable correlation between reason and revelation in derivation of authoritative orthopraxy. The controversial aspect of this attempt to affiliate law and ethics was whether such a relationship could be shown to be solely the product of a religious worldview firmly founded upon scriptural authority, or whether it was possible to guide human moral conduct without reference to any revelatory sources. The emerging idea was about the relationship between reason and revelation to provide continuous guidance for the developing and culturally diverse Muslim societies, principally by taking into consideration historical circumstances that determined the contemporary social and political practice. The main thrust of the classical Muslim intellectual development was to anchor moral epistemology reliably within the primarily religious sources to underscore its inseparable and logical relationship to interpretive jurisprudence that provided time-specific responsa in general to resolve pressing issues related to everyday practice. The universal moral truth that was endowed by God’s nature (fitrat allah) in humankind and was acquired rationally did not require religious affiliation or scriptural justificatory reasoning. The more immediate religious inquiry was not to explore the sources of human conduct; rather, it was to comprehend divine will as it related to human life in this and the next world. God’s will, as declared by the revelation, was embodied in the divinely ordained system that would define and formulate the boundaries of orthopraxy. This was the scope of the emerging field of interpretive jurisprudence (al-fiqh) in the classical period.

thanks