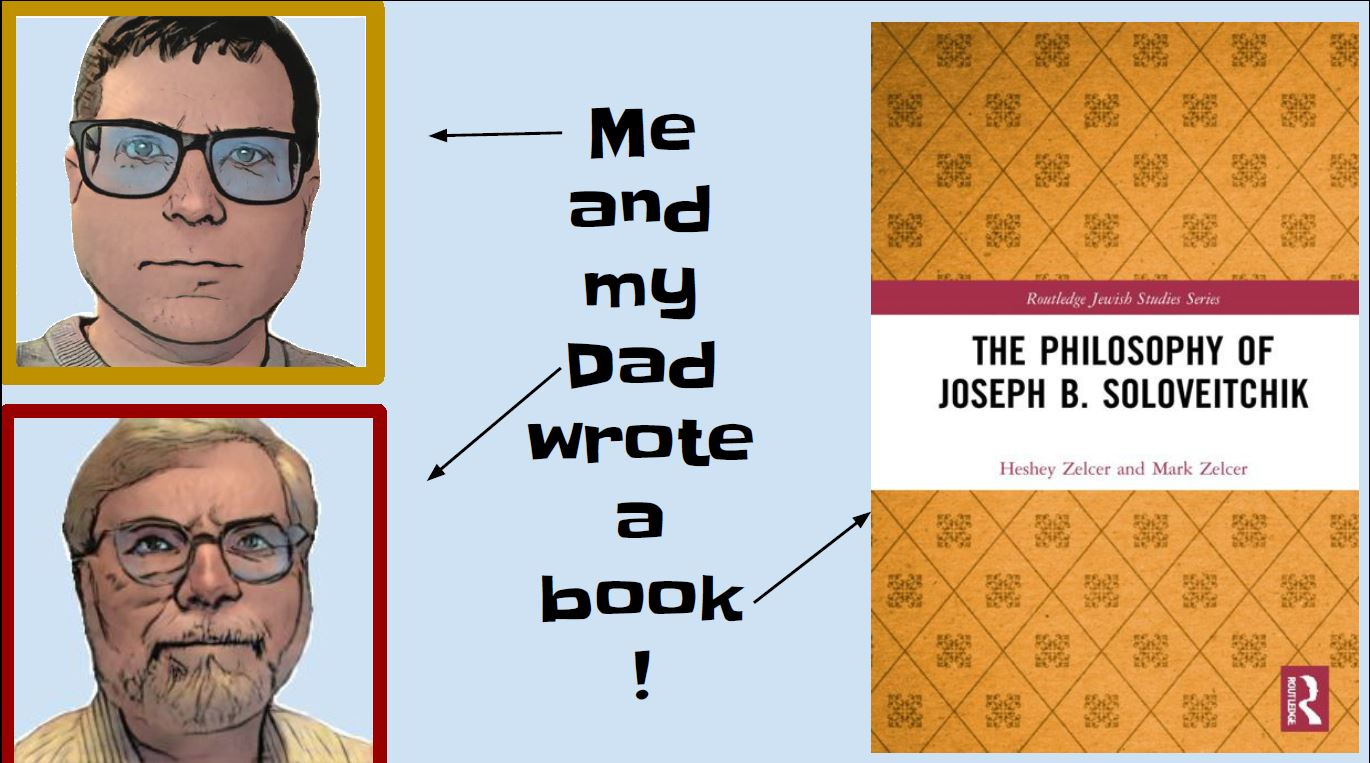

Heshey Zelcer and Mark Zelcer (Queensborough Community College, CUNY), "The Philosophy of Joseph B. Soloveitchik"

Routledge, 2021 - paperback edition, 2023

The Philosophy of Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

This post is written by Mark Zelcer.

The book’s authors are Heshey Zelcer and Mark Zelcer.

Mark Zelcer is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Queensborough Community College, CUNY.

Heshey Zelcer had a career in the software industry and is now on the editorial board of the Journal of Ḥakirah. He has authored three books and numerous essays on Jewish topics.

The book is Published by Routledge, 2021; paperback 2023.

Soloveitchik has a comprehensive religious Jewish philosophical system which we reconstruct from his books, lectures, and essays. The book’s emphasis is on describing how his work hangs together as a coherent philosophical program.

Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was a scion of an important European Rabbinic dynasty. Primarily educated in Talmud by his father in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus, he eventually went to the University of Berlin and earned a doctorate in philosophy with a dissertation on Hermann Cohen’s neo-Kantian epistemology. Just before WWII he moved to the US, took a position as a community rabbi and set up a Jewish school in Brookline, MA. He taught at Yeshiva University in New York for 40 years as lecturer and dean. He ordained over 2000 Rabbis and is widely considered the original spiritual and intellectual leader of Modern Orthodox Judaism.

To understand Soloveitchik’s philosophical program, there is some necessary background into Jewish law, Jewish philosophy, and the philosophical and psychological landscape of 1920s Germany.

Soloveitchik’s philosophical program distinguished between indigenous Jewish philosophical questions and those questions it inherited from non-Jewish sources. He focused on a specific question from classical Jewish thought about the nature of the commandments.

First bit of background: (The words in the bubble are a paraphrase.) Soloveitchik re-interpreted the “ta’amei ha-mitzvot” question, a question that has been part of Jewish philosophy since antiquity. Originally it asked “What are the reasons for the Jewish commandments?” He instead asked “What is the experience of the commandments?” The reinterpretation is more natural in classical Hebrew. The word “ta’am” can mean both “reason” or “experience of taste.”

Second bit of background: understand that Soloveitchik was wholly focused on Jewish Law. He sees Jewish Law as the only source from which Jewish philosophy can emerge. The word for Jewish Law is “Halakhah.” Soloveitchik construed “Halakhah” broadly to include Law, classical Jewish texts, mysticism, and homiletics.

Third bit of background: As the hard sciences were becoming mathematical and the social sciences were coalescing as independent disciplines, each science developed its own ontology. Soloveitchik espoused an ontological and epistemic pluralism. Each discipline decides what objects are meaningful to quantify and subsume under its laws.

Final bit of background, from early German psychoanalytic theory: There are idealized personality types. Everyone is made up of a combination of them, but expresses one dominantly. Soloveitchik adapted this from Eduard Spranger, but the idea appears prominently other psychologists of the time. (This theory survives in things like the Myers-Briggs inventory.)

And here begins Soloveitchik’s philosophical program: Halakhic Man (more precisely, we claim, homo halakhicus, Halakhic Person) is someone whose ontology is created by the objects and constraints of Jewish Law and whose phenomenology is generated by interacting with the objects of his world. Halakhic Man’s personality is unique and does not fit the idealized categories in the personality psychology literature.

Halakhic Man’s ontology is constructed from the categories of Jewish Law. Thus for him, there is no field or tree or apple, but instead a public domain with a fruit tree and fruit. Those are halakhically relevant objects. Things are relevant to Halakhic Man like aesthetic, legal, and natural concepts that have no relevance to those whose ontology is shaped by other disciplines. (Soloveitchik’s book Halakhic Mind provides much of the outline of this part of his philosophical system.)

The ideal Jew (and also the ideal person) is one who is never comfortable. They perpetually swing between various psychologically incompatible mindsets. For example, someone may dedicate themselves wholly to grasping the technical minutiae of the Law. Then at some point they realize that they are neglecting their spiritual life. At which point they completely give themselves to that task until they realize that they are neglecting the Law, and swing back, and again... This is a perpetual internal dialectic that never resolves in any type of synthesis. This is described in Soloveitchik’s “Catharsis.”

Soloveitchik’s most famous essay “Halakhic Man” explains that Halakhic Man is a personality type that perpetually vacillates between the personality of “Cognitive Man,” a well-articulated personality type, and the personality of “homo religiosus” (“Religious Man”), also clearly spelled out in the personality psychology literature. Halakhic Man has aspects of both, but is neither a synthesis or hybrid of the two.

Soloveitchik’s essay “The Lonely Man of Faith” contrasts the two portraits of Adam in the Biblical book of Genesis. The first version of Adam (Gen 1:26-28) is described as a practical creator who asks “How-questions” and the second version of Adam (Gen 2:7-8, 15) is a seeker asking “why-questions.”

In his essay “Majesty and Humility” Soloveitchik shows the Biblical Abraham (among others) as sometimes described as Humble and sometimes Majestic. He was Humble when forced to sacrifice Isaac and Majestic when told he will spawn great nations. Ideally one is sometimes Majestic and sometimes humble, though one cannot be both simultaneously. One perpetually goes back and forth between the two in a never-ending unresolvable dialectic.

Two of the main questions of Soloveitchik’s Jewish philosophical program are “How does fulfilling religious commandments give rise to the phenomenology of Halakhic Man?” and “How do Halakhic Man’s phenomenology and ontology interact to create one another?”

The answer: Using the objects that Halakhah creates in the ritualistically prescribed way, each generates a specific feeling or mental state.

Halakhic Man’s phenomenology is the combined interaction of all the feelings and mental states generated by studying and observing the Halakhic Law, and seeing the world with the Halakhah’s ontological categories.

We argue, then, that Soloveitchik understands the goal of Jewish philosophy is to spell out, understand, and explain the relationship between the Jewish concept of being and an authentic Jewish phenomenology as given to Halakhic people.

Beside his main philosophical program, he addressed other pressing timely philosophical issues. Writing near the birth of the State of Israel, Soloveitchik embraced a visceral Zionism, motivated by the Holocaust and the 2000-year-old dream of Jews returning to the Holy Land. His Zionism is religious, not political, social, or cultural. It is religious, but not messianic or eschatological. It is religious because the state of Israel has Halakhic significance. (Our book provides background on the history of Zionism, religious Zionism, and the dominant religious anti-Zionism of Soloveitchik’s time.)

In an essay “Confrontation” Soloveitchik explains why he does not approve of Jews entering into theological discussion with Christians. He was wary because of the long Church history of anti-Jewish persecution. He argues that Jewish history does not authorize any change in Judaism in light of any discussion with other religions; and ultimately, religions are incommensurable. The intellectual categories used in one religion are meaningless for the other. They cannot communicate. (In our book we present the context of the debate that Soloveitchik’s stance generated amongst Orthodox Jews.)

Now available in paperback and e-reader formats. Available wherever fine reading material is sold. No purchase necessary. Void where prohibited. Buy the book. Get your library to buy the book. Email me for a review copy.

This slideshow is also available here.

Thanks so much for this post (and the illustrations provide a nice touch). I look forward to reading the book!

It's likely that you touch on this issue in the book, but I'm just curious what you think of the oft-contrasted approaches of Soloveitchik and Heschel vis-à-vis interfaith dialogue. Here's the bumper sticker version of Heschel's perspective (relying on his so-called "depth theology") as I understand it: while Jews and Christians cannot meaningfully meet on the cognitive level of contested doctrines (like the trinity or incarnation), they can meaningfully meet on the in some sense more fundamental level of the phenomenology of encountering the Ineffable. What I'm wondering specifically is why you think this approach wasn't congenial to Soloveitchik. It seems like a genuinely religious place of potential meeting (rather than just the "secular" sphere of meeting that he permitted), but doesn't seem to threaten assimilation or anything like that. Thanks!

This book looks amazing! Its being added to my long term wish list - hopefully when I finish college I'll be able to afford it.