Julian Ratcliffe (Balliol College, University of Oxford), ‘Genealogy: A Conceptual Map’

European Journal of Philosophy, 2024

Genealogy has received much philosophical attention in recent years. However, that attention has at times confounded as much as it has clarified. My new paper, Genealogy: A Conceptual Map, charts the conceptual waters of genealogical inquiry by presenting a new two-dimensional typology of genealogy. Along the way, the paper also aims to disentangle some pervasive confusions in the literature and respond to two challenges genealogical inquiry faces.

In its most expansive sense, a genealogy is a form of philosophical inquiry which aims to explain some object of investigation – a belief, practice, concept, institution, etc. – in terms of its history, origins, or process of development. Such explanations figure in our reasoning all the time. So-called ‘just because’ arguments (“You think The Simpsons is the best TV show ever made just because you used to watch it with your father!”) are a paradigm as they aim to trace some belief (that The Simpsons is the best show ever made) back to its origins (pleasant memories of spending time with one’s father) as a means of explaining why one holds the belief.

Notice, however, that the intended effect of claiming that one thinks The Simpsons the best show ever made ‘just because’ of some fact about the origin of the belief is to implicitly (and often explicitly) challenge the rational status of the reason publicly professed for the belief. The tacit claim is that while one might claim to rate the show so highly for the quality of its jokes or cultural commentary or what have you, the ‘real’ reason they like it is because of factors that have nothing to do with the show at all, namely affection for their father.

This feature of genealogical inquiry is typically cashed out in terms of epistemic reliability. The suggestion is that since the TV watcher in question would have thought whichever show they had watched with their father the best ever made regardless of the quality of its jokes or its cultural commentary, their fondness for The Simpsons isn’t reliably sensitive to the reasons standing for or against rating it so highly. And while it is entirely benign to arrive at a belief about the quality of a TV show on the basis of contingent features of our personal histories, the argument generalises to contentious ethical and political beliefs demanding rational justification. (Compare The Simpsons case above to “You believe homosexuality is wrong just because your father was a preacher!”.)

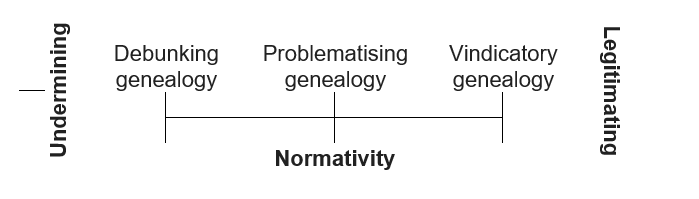

Attempting to undermine the rational status of a belief by showing that it descends from some unreliable belief-forming mechanism is what characterises what is commonly called debunking genealogy. To those unfamiliar with the literature, debunking genealogy is often considered genealogical inquiry’s central formulation. Nevertheless, genealogical reasoning can also be used to legitimate our beliefs. While this can, of course, be done by showing a belief to originate in a reliable belief-forming process, it can also be done by showing that believing it serves some function in contributing to the achievement of some practical end. Insofar as it is an end we endorse under reflection, the belief is to that extent vindicated. This form of genealogical inquiry is what Bernard Williams calls vindicatory genealogy.

Together, debunking and vindicatory genealogies form the poles of what I call the bipartite typology. The bipartite typology is a way of organising genealogies according to their normative objectives, that is, according to whether they undermine or legitimate our beliefs. This way of organising the literature has predominated since the publication of Williams’ Truth and Truthfulness.

The problem, however, is that the bipartite typology does not seem to be able to account for some of the most important (both historically and philosophically) genealogies in the literature. For instance, the primary objective of Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality is not to show that Christian moral values are the product of unreliable belief-forming processes, but rather to interrogate the value of moral values themselves by examining the various functions that morality’s constituent elements have served over the course of their development. Nietzsche is less concerned to critique Christian morality because it lacks rational foundation, but rather because of the way (he claims) it hinders the achievement of human greatness. Yet even though it is not primarily concerned with the rational status of our beliefs, Nietzsche’s Genealogy is typically thought of as a debunking genealogy because the paucity of the bipartite typology means we lack the conceptual resources to grasp its critical import.

In response to this shortcoming, recent contributions to the literature by Allen (2008) and Koopman (2013) have staked out a third category of genealogical inquiry, what they call problematising genealogy. Rather than taking aim at the rational status of our beliefs, problematising genealogy aims to transform the seemingly uncontroversial elements of our epistemic lives into problems of philosophical concern by highlighting the contingency of their construction. The objective is thus less to undermine our beliefs than it is to create the space for critical reflection on the previously invisible, putatively given elements of what I call the background frameworks against which our beliefs can be recognised as intelligibly doxastic at all. That problematising genealogies such as Nietzsche’s (as well as, among others, Foucault (1978) and Butler (2006)) are sometimes thought to be of a piece with debunking genealogies is thus to commit what I call the debunking/problematising conflation.

Introducing problematising genealogy to the picture means that we must reorganise our typology. Since it does not make sense to straightforwardly say that our background frameworks are irrational (as they include the very standards of rationality that would be deployed in such a judgement), both Allen and Koopman contend that problematising genealogy is normatively neutral. We can hence situate problematising genealogy between debunking and vindicatory genealogies to create a tripartite typology which, like the bipartite typology, organises the literature along a normative spectrum according to the objectives of the genealogies which populate it (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The tripartite typology.

The problem now facing us is that it is not at all clear what it means for a genealogy to be normatively neutral. Indeed, as Robert Brandom puts it, even the genealogist must view herself as presenting determinate accounts about something, “accounts that aim to satisfy the distinctive standards of intelligibility, adequacy, and correctness to which they hold themselves” (Brandom 2019, 577). This means that even the genealogist, on pain of meaninglessness, must implicitly assume some standards of acceptability for her genealogy, standards which exert determinately normative authority over her account.

Additionally, Brandom (2019), Queloz (2021), and Dutilh Novaes (2015) have recently developed distinctive forms of genealogical inquiry. Like problematising genealogy, these genealogies examine the constitution of the background frameworks that structure the doxastic landscape. But unlike problematising genealogy, they do not function to open up new possibilities for critique. Rather, they aim to retrospectively explicate the background norms governing our present discursive activity or the practical needs our concepts serve so that we might improve their functionality. I call this form of genealogical inquiry rationalising genealogy because it hinges upon a retrospective rationalisation of the discursive and practical traditions we matter-of-factly inherit over the course of history.

This brings us to the second confusion in the literature: the problematising/rationalising conflation. This conflation arises because the force of problematising genealogy’s critique hinges on its ability to expand the field of discursive possibility beyond that presently conceivable, a feature it shares with rationalising genealogy insofar as the latter makes possible new forms of discursivity. However, whereas problematising genealogy makes good on that promise through unguaranteed experimentation, rationalising genealogy operates by making explicit the norms already present in our conceptual practices. This distinction is overlooked, however, because in organising the literature according to the tripartite typology, those genealogies which do not obviously aim to undermine or legitimate our beliefs are erroneously thought to constitute a unified type characterised by their putative normative neutrality.

In order to accommodate rationalising genealogy while abiding by the requirement to give up an unworkable notion of normative neutrality, I propose a two-dimensional typology of genealogy (Figure 2). On this picture, we can enrich our conceptual repertoire by adding a second dimension of analysis to the normative dimension around which both the bi- and tripartite typologies are organised. This second dimension of analysis makes visible the objects that various genealogies target – our doxastic states and the background frameworks against which they stand out in relief – and the way they are structured to investigate those objects.

Figure 2: The two-dimensional typology.

There are two primary benefits of adopting the two-dimensional typology I propose. Firstly, straightforwardly embracing the normativity of problematising and rationalising genealogies gets them into the correct conceptual shape for deployment in projects of critique or constructive analysis respectively. The downstream benefit of doing so is that we can simply sidestep the question of genealogy’s normative foundations which has preoccupied so much of the recent critical theory literature.

And secondly, being able to distinguish genealogies according to their objects of analysis enables us to better understand the two main objections levelled against genealogy: the genetic fallacy and self-defeat objections. We can now see, on the one hand, that the genetic fallacy, which only lands when brought to bear on items with propositional content, simply does not apply to problematising and rationalising genealogies as they do not target our beliefs at all. On the other hand, we can see that while the self-defeat objection poses a genuine threat to the coherence of debunking genealogy, it stands in a significantly ambivalent relation to problematising genealogy given that – as its attention to our background frameworks reminds us – explanation must come to an end at some point, precisely where we draw it to a close a function of the practical purposes we manifest in inquiry.

The overarching value of my paper lies in its ability to help us navigate an exciting and rapidly growing literature. My intention is not to present an exhaustive analysis of genealogy as a form of philosophical argument: there are, of course, genealogies which straddle the internal (and presumably external) boundaries of the two-dimensional typology I propose. But my paper is not an exercise in conceptual analysis in service of the goal of establishing the necessary and sufficient conditions for a genealogy to count as a member of one or another of the categories I identify. Rather, the intention is to highlight the often unrecognised diversity of genealogies, the distinctive of argumentative purposes they are put towards, and potential ways of overcoming the challenges they face. For that, a map is just the tool we need.

Bibliography

Allen, Amy. 2008. The Politics of Our Selves: Power, Autonomy, and Gender in Contemporary Critical Theory. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Brandom, Robert. 2019. A Spirit of Trust: A Reading of Hegel’s Phenomenology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Butler, Judith. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dutilh Novaes, Catarina. 2015. ‘Conceptual Genealogy for Analytic Philosophy’. In Beyond the Analytic-Continental Divide: Pluralist Philosophy in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Jeffrey A. Bell, Andrew Cutrofello, and Paul M. Livingston. New York, NY: Routledge.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Koopman, Colin. 2013. Genealogy as Critique: Foucault and the Problems of Modernity. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Queloz, Matthieu. 2021. The Practical Origins of Ideas: Genealogy as Conceptual Reverse-Engineering. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

also, later, once the thickets have been cleared with a map, a taphonomy of fixed points might be a better model, more practical than most genealogies allow

this is great so useful "charts the conceptual waters of genealogical inquiry by presenting a new two-dimensional typology of genealogy."