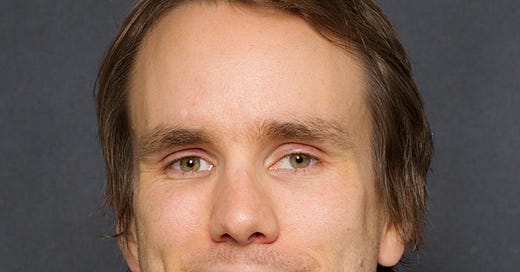

Lars Moen (University of Vienna), “Against Corporate Responsibility"

Journal of Social Philosophy, 2023

By Lars Moen

We commonly hold individuals morally responsible for their actions. We praise them for good actions and criticize them for bad ones. But when individuals form a group, many philosophers think it will not suffice to hold only the group members responsible for their group’s actions. When a corporation pollutes a river, for example, we should not expect only individuals to be responsible. At least some of the responsibility is rightfully ascribed to the corporation itself. By taking this view, we endorse what is commonly called “corporate responsibility”.

I reject this view in my paper “Against Corporate Responsibility”. I do so by showing how it rests on an implausible and incomplete account of individual agency. When we appreciate individuals’ capacity, as group members, to act with an eye on how they affect their group’s decision making and actions, we shall see why we are mistaken to hold the group responsible. We should instead hold individuals responsible based on their understanding of how the consequences of their actions depend on the actions of others.

Let me explain by exploring a key example in Philip Pettit’s influential defense of corporate responsibility. Pettit bases his interesting view on the observation that it may simply be impossible for a group to function strictly on its members’ judgments. In his example, the committee of an employee-owned firm decides on whether to sacrifice the employees’ pay raise to finance new safety measures in the workplace. The three committee members agree that three reasons are separately necessary and jointly sufficient for deciding in favor of the safety measures and the pay sacrifice. But they do not all hold the same view of these reasons. First, only Members A and B think the workers are currently in serious danger. Second, only Members A and C think the proposed measures would actually improve the workers’ safety. And third, only B and C consider the pay sacrifice bearable for the employees. Since none of the members accept each of the necessary conditions, none of them supports the pay sacrifice. But a majority accepts each reason. So, by following majoritarian reason-based collective decision making, the committee will decide in favor of a pay sacrifice that each committee member rejects.

Who is then responsible for the decision? Pettit thinks each committee member can reasonably say “Don’t blame me; I didn’t want this result”. Only the committee as a whole formed the judgment in favor of the pay sacrifice. Pettit therefore argues we must hold the committee itself responsible as a moral agent capable of forming its own judgments.

But Pettit and other defenders of corporate responsibility let the individuals off the hook too easily. They crucially overlook possible ways in which individuals can behave within their group to bring about their desired outcome. In Pettit’s example, let us first consider how the issues the group members vote on were selected in the first place. Someone would have set the agenda. This person, or persons, may have also chosen the decision procedure – reason-based, as in the example, instead of voting directly on the outcome. With a sense of the group members’ judgments of different issues, this agenda setter could then effectively determine the outcome. Had some other reason appeared on the agenda, a majority may have rejected it, and the group would have made a reason-based decision against the pay sacrifice.

We should further ask why the group members voted the way they did. Let us not forget that it was their votes that led to the pay sacrifice, even though they did not vote for it directly. If they cared sufficiently about preventing this outcome, they could have rejected each of the reasons they knew could support it. Had they done so, they would have been sure not to contribute to the outcome. By voting as they did, however, they knew they might contribute to the decision favoring the pay sacrifice. Pettit’s example therefore actually shows why expressing opposition to an outcome may not be enough to escape responsibility for it.

More generally, when we ascribe responsibility for a group action, we should not hold the group itself responsible just because its members do not express support for the action. We should look at how individuals failed to take opportunities to prevent the action, or at least not contribute to it.