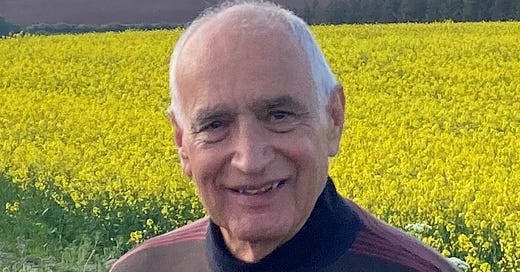

By Paul Gomberg

After over 250 years of anti-racist struggle, why does anti-black racism persist in the United States (US)? Anti-Racism as Communism marshals the resources of revolutionary Marxism to explain this persistence and offer a way out: capitalist society benefits from the racial organization of labor; only communist society— where we flourish by contributing to one another’s flourishing—can end racism.

Racist societies—where some marked out by racial categories have worse (shorter, less healthy, etc.) lives on that account—create hyper vulnerable workers. Being more vulnerable, hence more easily controlled, these workers toil to the benefit of capitalists. Divided by race, nearly all workers suffer harm. But racism is good for profits: capitalists operating in racist societies have a competitive advantage over capitalists operating in non-racist societies.

Because racism is functional (enhances capitalist profits) racism re-emerges in new forms in response to anti-racist struggles. The conclusion that racism is functional emerges from a review of the role of black labor in US history and of anti-racist working class struggles largely unknown to today’s anti-racists. Those struggles were defeated by capitalists and the state they control. The greatest struggles were led by the Communist Party (CP) in the US during its heyday from 1930 through the mid-1950s, and the government-led suppression of the CP’s anti-racism was a disaster for the working class, particularly black workers. The story of those wonderful struggles is omitted in most history curricula and is known mostly to labor historians. Anti-Racism as Communism highlights it.

Anti-Racism as Communism develops a communist anti-racist philosophy based on this historical background.

While people living in racist society “naturally” think of racism as interracial (the oppression of one racial group by another), it is not. Rather racist social organization is created and recreated by people with political power. These are capitalists and their political representatives. While capitalists are often split by factions, they do not cede power to the working class. Those without power often adopt racist (by those less oppressed) or resentful (by those more oppressed) attitudes toward other powerless people. These attitudes and racist actions stemming from them are not the cause of racist society but consequences of racist society. Hence racism is wrongly thought of as an interracial phenomenon. It is harm resulting from how one is identified racially.

Then why does it seem so natural to think of racism as interracial? We tend to think this way because we accept the racial categories of racist society as applying to ourselves, we think of ourselves as black or white. When people accept an identity, they tend to favor others with the same identity (a finding of social identity theory). Intuiting that this is so, we naturally think racist society is a result of whites having more power and favoring whites. But this is wrong. It confuses racist society with in-group favoritism and intergroup rivalry. Such favoritism and rivalry are real but are not the same as racism. The harms of this confusion are brought out by showing how anti-racist struggles at Chicago State University (CSU)—where most students and top administration were black—were limited because many did not recognize attacks on black students by black administrators as racist: they accepted the racial identities assigned to them and hence thought of racism as interracial. To combat racism at places like CSU we must strive to alienate racial identities, to understand the categories we are placed in by racist society as “our enemies’ name for us.” The categories themselves are harmful to our interests.

What emerges from this argument is race-centered Marxism that is aracial. That is, politically working-class unity requires us to lead with anti-racist struggle—a conclusion from the anti-racist work of the CP. However, prominence of racial identities—our acceptance of racial categories—undermines anti-racist struggle: where the direct agents of racism are black, acceptance of racial identities makes it harder to recognize racism; where they are not black, that acceptance limits the struggle, causing people not identified as black to believe that harms to black people are not to their people. Hence race-centered Marxism is race-centered politically but class-centered and aracial in the identities of activists.

What are we fighting for? What would a society without racism be like? It cannot be one where the burdens experienced by black people in racist society are shifted to others; there is simply no way to build a practical movement to do that. So the proposals of Elizabeth Anderson, Charles Mills, and David Lyons fail to give us a viable way forward. We must reconceive how we live together. My 2007 How to Make Opportunity Equal begins to sketch the answer. If we think that what makes life good is material possessions, then there is no way forward, for material things will always be in limited supply. So what makes life good must be things that can be available in unlimited supply, where there is as much of them as we could want. Our opportunities to develop our abilities, to contribute our developed abilities to the good of others, and to earn esteem from our contributions—those could be in unlimited supply provided we share labor in a way that overcomes the sorting of workers into skilled (including professionals) and unskilled and of children into winners and losers. That is, whatever labor cannot be made to engage our capacities for mastering complexity and exercising creativity would be done by all. Then everyone can flourish together. Each would have opportunity to engage in complex creative labor and make contributions to our common good. In such a communist society each has a natural reason to want others to develop their abilities and to flourish through labor, for the flourishing of each advances the flourishing of all. This vision of communism inspired Marx—from his early Comments on James Mill to the Manifesto’s “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” to the “Critique of the Gotha Program’s” proposal that in communist society labor would be “a vital need.”

However, an objection lurks: given what has happened to the Soviet Union and in China, how can we have any reasonable hope for such a communist society? Hope for communism can be reasonable only if we can identify why Soviet and Chinese revolutions failed to lead to communism and show that these flaws are correctable. If we focus on China, we can see that this is the case. While in the late 1920s Mao’s army was living in a communist way and soldiers reported feeling “spiritually liberated” by the egalitarianism, by 1937 the CCP began introducing material distinctions between lower and higher ranks, eventually separate dining rooms with better food for officers, then higher pay for party leaders. Party membership became an avenue to social advancement. The party drew more Chinese nationalists to its ranks. So the great communist experiment in the Great Leap Forward (1957-59)—the free sharing of many essentials, including food—was undermined by emphasis on industrialization within the villages. Then when bad weather greatly reduced grain production, provincial party functionaries lied to look good to higher ups and shipped grain to the cities leading to mass starvation in their areas.

However, at the same time there was within the party a genuine communist spirit among many local cadre, who said, “If something difficult and dangerous needs to be done, communists go first; if something good is desired by all, communists go last.” If communists had never recruited nationalists to the party, if they had retained the egalitarianism of the late 1920s, if they had retained that egalitarian communist spirit, communism could have succeeded. There is reasonable hope.

However, despair that we can ever have a society without racism may also be reasonable. Even if this is so, we should prefer reasonable hope of communism. It sets the highest possible ideal for our lives now and leads to the best life possible for us now.

So that’s my book. One problem: Bloomsbury is now issuing it only in a very expensive hardback ($120 at Amazon, $108 at Bloomsbury’s website) or as a slightly cheaper electronic version. Capitalist publishers gotta make their money. Unless you are very rich, what you can do now to get and read this book is to have your university or a public library order it. If they acquire the (cheaper) electronic version, there is the advantage that unlimited numbers with library privileges can read it together.

To get a bigger taste of what I have done the widget for the book is https://bloomsburycp3.codemantra.com/viewer/652d1280f4428a00018aaca7.

What, pray tell Mr. Wollen, "seems unlikely?" My decades-long research and study of Marx and Marxism (and its multifarious variants) is in utter agreeance with that which you cite as, "unlikely" (viz., "capitalist society benefits from the racial organization of labor; only communist society--where we flourish by contributing to one another's flourishing--can end racism.").

“capitalist society benefits from the racial organization of labor; only communist society— where we flourish by contributing to one another’s flourishing—can end racism.”

Having just watched Bridgerton, this seems unlikely