Filipa Melo Lopes (University of Edinburgh), "What Do Incels Want? Explaining Incel Violence Using Beauvoirian Otherness"

Hypatia, FirstView

It’s been nearly a decade since 22-year-old Elliot Rodger stabbed and shot 7 people, including himself, in Isla Vista, California. In a lengthy manifesto of over 130 pages, Rodger laid out an epic tale of rejection, isolation, resentment, and vitriolic misogyny. His so-called “Day of Retribution” has inspired several other mass killers and has become a foundational moment of what is now discussed as ‘incel’ extremism — violent attacks connected to online communities of self-proclaimed ‘involuntary celibate’ men.

Ever since Isla Vista, feminist commentators have insisted that the motivations behind these attacks cannot be understood solely through the lens of mental illness. Instead, incel violence must be seen as a reaction against recent social transformations. According to these feminists, what incels want is a return to a world where women can be treated as sex-objects or loving servants. What is bothering them is not being single or sexless, but the fact that women today have independent lives and feel no sense of duty toward them.

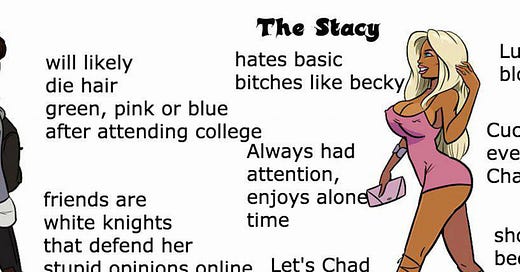

Although I agree that incel violence is a gendered phenomenon, I argue that these analyses have failed to capture a central feature of incel attackers: their disconcerting ambivalence toward women. The same “hot, beautiful, blonde” women men like Rodger desire are also said to be unintelligent, vain, fake, and sociopathic (Rodger 2014, 132). Incels idolize the oversexualized hyperfemininity encapsulated in the ‘Stacy’ meme. But they also single out ‘the Stacys’ not just for punishment, but for extermination.

I claim that what incels are after is what Simone de Beauvoir called a feminine “Other” — an impossible creature, closer to a nymph or mermaid than to a sex-doll or a dutiful wife. An “Other” is a device through which men can achieve a certain sense of themselves. She is a repository of their brightest dreams, but also of their worst nightmares. On this Beauvoirian reading, incel violence is not a backlash against feminism, but the predictable implosion of a common form of masculine self-alienation.

Indeed, the problem lies not just in how men like Rodger see women, but, fundamentally, in how they see themselves. Like all human beings, they are caught in a bind between the need to act and the risk of action. We all want to do things in the world that will garner admiration and make us feel proud, whether it is getting a degree, painting a room, writing a book, or rebuilding a car. But there is an unavoidable danger of failure that comes with striving to achieve anything in life. We would all like to be successful, but success requires taking risks. This tension is something that everyone must learn to live with. But men are often encouraged to avoid it by adopting a distorted view of themselves as uncriticizable — as always able to control anything, even the uncertain judgement of others. Elliot Rodger, for instance, was convinced he was “a living god” (135) and that life was a competition he would obviously, somehow, win. But this does not make sense. To experience oneself as praiseworthy, one must also be open to the risk of failure. What men like Rodger want is to be heroes, regardless of their actions. And this means that he ends up insisting he is “destined for great things” (79), even while he drops out of school, refuses to get a job, and lives as shut in.

Woman as “Other” becomes then his “marvellous hope” of somehow feeling recognized as this special being in the absence of any actual accomplishment (Beauvoir 2011, 217). To fulfil this function, this dream girlfriend must be another human consciousness who can praise Rodger, but not a full person who can spontaneously criticize him. Her approval must be fully conquerable. She must be an entity that can be picked up like a piece of fruit or a flower, but who can then genuinely smile back at you like a person. This is why, for Beauvoir, “nymphs, dryads, mermaids” and other animistic goddesses are paradigmatic “Others” (174–76). They are natural objects animated by a human consciousness.

But nymphs and mermaids are not real and this feminine “Other” is an impossible fantasy. The more men pursue it, the more they doom themselves to a bitter disenchantment. Just like you cannot be a hero without doing heroic deeds, you cannot expect someone to praise you without the possibility of criticism. The risk of negative judgment always creeps back in. For example, consider Rodger’s description of a woman he sees on the beach:

she was like a goddess who came down from heaven. . . . I was scared. I was scared she might view me as nothing but an inferior insect who’s [sic] presence ruins her atmosphere. Her beauty was intoxicating! And then, just as we passed each other, she actually looked at me. She looked at me and smiled. . . . I had never felt so euphoric in my life. One smile. One smile was all it took to brighten my day. The power that beautiful women have is unbelievable. (Rodger 2014, 76)

If her regard can bestow ultimate triumph, this goddess can also bestow ultimate failure. And when his feminine saviours fail to anoint him as a hero, Rodger’s fear grows. Beautiful women become hateful enemies and violence becomes the only way of accomplishing himself through them: “on the Day of Retribution, I will truly be a powerful god” (135).

So, even though incels talk obsessively about women, looking closely at murderers like Rodger reveals that their struggle is mainly with themselves. Their anger at their ‘celibacy’ is often an anger at being just part of the crowd. Violence becomes a desperate attempt to gain control over the world and achieve the recognition that they feel they deserve. Countering incel radicalization requires then pushing back against the idea that women are the answer to men’s problems. It also requires men to stop thinking of themselves as “living god[s]” and instead cultivate a healthy sense of competition, personal responsibility, and humility.

You can read the full paper here.

References

Rodger, Elliot. 2014. My twisted world: The story of Elliot Rodger.https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/1173619/rodger-manifesto.pdf

Beauvoir, Simone de. 2011. The second sex. Trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier. New York: Vintage Books

I think that inceldom is a phenomenon of significant philosophical interest, and I hope that this paper helps draw forth further interest in it from philosophers. Nevertheless, I worry that the paper seems to generalize incels in a disparaging and overbroad way. One question I'd raise is how making sweeping claims about "what incels are after," on the basis of a manifesto by a single violent extremist, is in principle all that different from, for example, making sweeping claims about "what Muslims are after" on the basis of the words and actions of Osama bin Laden.

Perhaps you'd say that incels are, by definition, woman-haters (maybe among other things), and that this definitional or conceptual fact makes the disparaging generalizations more apt. If so, then I think that there are some further worries to be raised, though that would take us into a different debate.